Hong Kong pro-democracy protests began in March 2019 in response to the Hong Kong government’s adoption of the Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters (Amendment) Bill 2019. Protests were held in response to the concerns that if the bill is passed, Hong Kong will become a part of mainland China’s legal system, losing its independence, right to privacy, and media freedom.

As police used excessive force to disperse protesters, protesters’ demands expanded beyond the withdrawal of the extradition bill to include an independent investigation into police brutality, the release of arrested protesters, the abolition of the phrase “rioters,” Carrie Lam’s resignation as Chief Executive, and direct election of the Chief Executive.

On June 9, 2019, about a million individuals took to the streets as part of a protest organized by the Civil Human Rights Front, a Hong Kong civil organization. It was the city’s largest rally in history. On June 16, almost 2 million people attended the rally, nearly double the number from the previous gathering.

Title of the protests

The protests are being named the “2019 Fugitive Offenders and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation Amendment movement”, the “Anti-extradition law protest”, or the “2019 Hong Kong protest”, or the “Anti-extradition protest”. The title “No China extradition(反送中) movement” comes from Taiwan’s Apple Daily, where it first appeared in the title of an article titled “Civil Human Rights First will hold a “No China extradition” march tomorrow.” From June 13, 2019, media outlets affiliated with Next Digital began to refer to the protests as a “reverse movement (逆權運動),” and on October 4, 2019, the protests were dubbed “Fight against violence (抗暴之戰).”

Beginning and early demands

In February 2018, Chan Tong-kai, a Hong Kong citizen, murdered his girlfriend, Poon Hiu-wing, herself a Hong Kong citizen, at Taipei’s Purple Garden Hotel. Although Hong Kong has long-standing extradition treaties with twenty countries, no extradition treaty existed between Hong Kong and mainland China since the People’s Republic of China’s government refused to recognize Hong Kong’s sovereignty. As a result, from the moment Chan returned to Hong Kong, Hong Kong authorities were unable to prosecute him for murder. On the recommendation of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region introduced the Fugitive Offender and Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Legislation (Amendment) Bill 2019 in February 2019. According to the administration, the bill’s purpose was to close a legal loophole and prevent the city from becoming a “fugitive’s paradise.” The amendment bill extradites suspects in Hong Kong to the jurisdictions of mainland China for trial. This raised concerns that the bill would deport “anyone in Hong Kong” to the mainland China for inquiry and punishment. Pro-democracy expressed worries that the bill would violate the principle of “One Country, Two Systems,” which has been in effect since 1997, and that applying the legislation of mainland China to the city would infringe on the judicial independence of Hong Kong. Residents of Hong Kong also expressed concern about mainland China’s judicial system and respect for human rights, citing mainland China’s history of repressing political dissidents. Residents organized large-scale rallies and campaigns, but the government of Hong Kong refused to drop the bill, resulting in a deadlock.

The bill was opposed by a wide range of groups in Hong Kong, including business, finance, academia, the legal community, and the press. They said that it would violate Hong Kong’s independent jurisdiction, which is protected by the principle of One Country, Two Systems, and that it would be used to punish people who have political views that don’t match those of mainland China and the Hong Kong government.

The protests, which began in March 2019, drew opposing announcements from a variety of sectors and sparked heated debate on social media, eventually bringing the amendment bill to widespread attention. According to the Civil Human Rights Front, the march on June 9, 2019 drew approximately one million and three thousand citizens. Following the large demonstration, Hong Kong’s executive chief declared via government press that the amendment bill’s second reading on June 12, 2019 will proceed as scheduled. On June 12, a group of citizens voiced their displeasure by surrounding the Legislative Council. The protesters’ initial demand was for the withdrawal of the extradition measure. “No China extradition” was a frequently chanted slogan at the rally.

Turning point

On June 16, 2019, a Hong Kong citizen named Marco Leung Ling-kit commits suicide in the face of a great march to “denounce oppression, revoke the unjust law.” He falls from Pacific Place, a retail mall, holding a banner that reads, “Release those arrested during the police-protester collision on June 12. Carrie Lam to resign as Chief Executive. ” Leung was the first person to die during the protest against extradition to China. Following his death, the Civil Human Rights Front and demonstrators changed their slogan from “No China extradition” to the following:

- The complete withdrawal of the proposed extradition bill

- The government should withdraw its labeling of protesters as “rioters.”

- The release of detained protesters and the dismissal of all charges against them

- An independent investigation into the police’s excessive use of force

- Carrie Lam to resign from the Chief Executive; implementation of genuine universal suffrage for the Legislative Council and the Chief Executive

This incident serves as a watershed moment in the protest. Protesters have expanded the anti-extradition bill protest into a movement expressing political and social displeasure and have shifted their focus to the police’s abuse of power.

The anti-extradition groups changed their name to “protesters” instead of ” demonstrators,” and the campaign grew to include more people from all walks of life in Hong Kong, while support around the world stayed strong.

Characteristics

Leaderless protest

There is no leader in the protest, and anyone can be the leader.

Organization

LIHKG : A website based in Hong Kong. The website launched in 2016, serving as the primary medium for citizens to discuss protest ideas and strategies during the 2019 Hong Kong protest, a leaderless protest.

Groups on Telegram

Telegram, an encrypted messaging service, was used as a communication tool among demonstrators and served as a covert driving force behind the protests. Telegram was used by protesters to communicate their plans, information, and thoughts. To interact and share information, protesters created hundreds of Telegram chat groups and channels. During the protest, concerns that the Chinese government could get protesters’ identities via the application prompted the search for a new messenger application with a stronger security system.

A Civilian Sentry

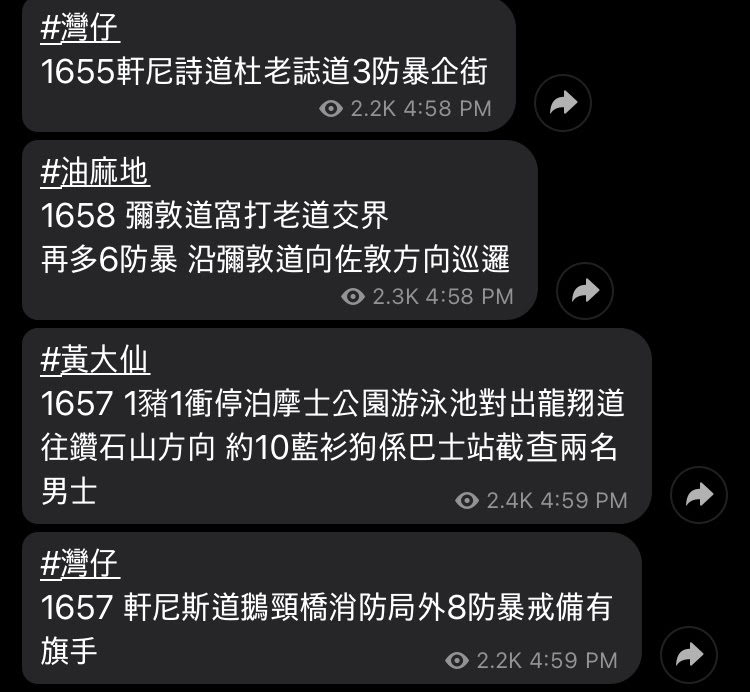

Telegram news sources for each region. Local residents who are familiar with their location keep the protesters updated on regional news, allowing demonstrators to stay informed and alter their plans in real time.

Flowers bloom everywhere

The phrase “Flowers bloom everywhere (遍地開花)” is derived from an idiom, which means that good events happen everywhere. It refers to the manner in which protests occur concurrently. Protesters gather at a spot near their home and then move to the location given previously to demonstrate. During the protests against the extradition bill, netizens staged a series of parallel rallies to disperse the police force. The largest “blooming” occurred on August 5, 2019, called the, “three-strikes movement” of August 5, 2019.

Public relations

Protesters employ a range of public relations strategies. It includes publicity for activities, explanations, advice, and tutorials, as well as international exposure, timeline development, and artwork. Public relations activities such as publicizing actions, advice, and tutorials are intended to facilitate the exchange of knowledge among demonstrators. International exposure and explanation help disseminate views and ideas. Creating timelines or artistic pieces serves as a record of history.

Airdrop

Not only did many people use internet flatforms such as LIHKG or Telegram chat groups to distribute publicity materials to other demonstrators, but many also used airdrop. It appears to be a way of disseminating electronic flyers, but it has several limitations. First, the recipients are restricted to individuals who own Apple products. Second, the airdrop function should be enabled.

온라인을 통한 시위 안내문

텔레그램을 통한 소식 전파

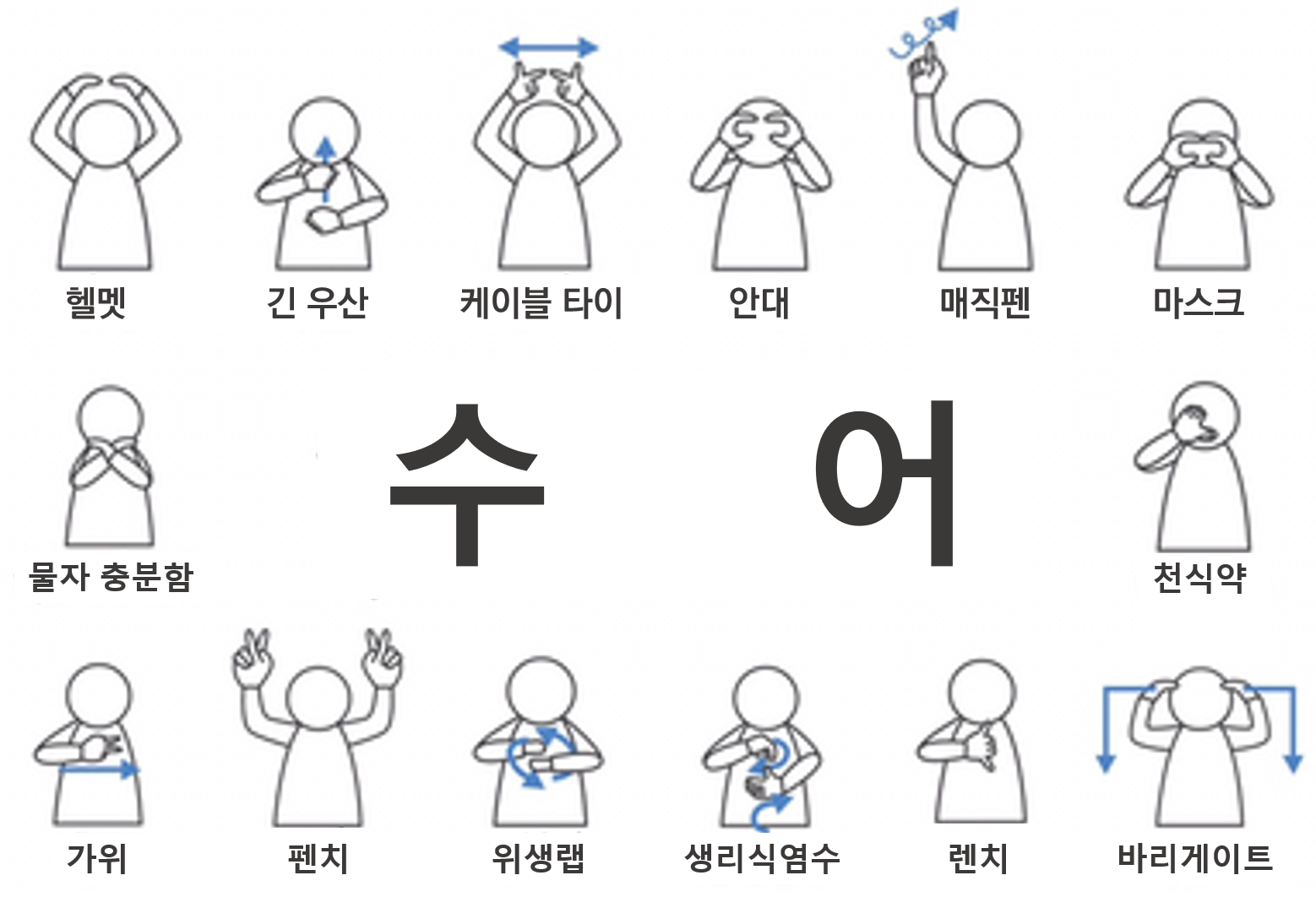

시위대가 사용한 수어들

Lennon Wall

The first Lennon Wall was created in Mala Strana, Prague, Czechoslovakia, in memory of John Lennon. Following John Lennon’s 1980 assassination in front of his house by a fan, a number of memorial ceremonies were held in front of a previously common wall. Of commemorate John Lennon and show unhappiness with the government, an unknown artist drew a portrait of him and the lyrics to his songs.

The Hong Kong Lennon wall refers to a wall that appeared during the 2014 Umbrella Revolution and the 2019 anti-extradition bill demonstration, affixed with Post-it notes holding messages and various publicity materials. It is also known as the democratic wall. The wall first appeared at the Government of Hong Kong’s headquarters in Admiralty, Hong Kong, on Harcourt Road. It is a significant landmark in the occupied area and a noteworthy work of art from the umbrella revolution. In June 2019, another Lennon wall reappeared, expressing opposition to the extradition statute and support for demonstrators. Following that, Hong Kong citizens created their own Lennon walls in local neighborhoods, expressing concerns about the city’s future and discontent with the process of amending the extradition law. Started in the Admiralty district, the Lennon walls have since expanded to eighteen sections of Hong Kong, serving as a ‘democracy wall’ for local communities. Among the walls, the one in the pedestrian tunnel near Tai Po Market Station is dubbed Lennon tunnel, with colored post-it notes stuck to each aisle’s wall.